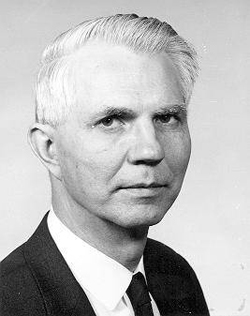

Dr. James G. Foulkes

Interviewed March, 1985

Int.: Dr. Foulkes, first of all, I understand there was quite a bit of controversy about the starting of the Medical School. Did that affect you in any way?

J.F.: Of course, I didn’t come to Vancouver until the end of the first year of the Medical School’s existence and so of course I quickly became aware of some of the cross- currents which were taking place at that time, which had led to the development of the school and the plans that were contemplated for its future. I became to some extent involved in those but wasn’t around when it started.

Int.: Mmm.

J.F.: I presume what you were referring to is the division between the supporters of the Dolman Report on the future of the medical school at UBC and the views sponsored by Fritz Strong, who was the proponent of having everything at the Vancouver General Hospital; Dolman, everything on campus. And we ended up with neither, with a divided school for a long period of time.

Int.: What were your expectations when you came? Were you expecting a school divided or one totally at the university?

J.F.: When I came, the impression that I gathered was that this issue had been resolved in favour of a united medical faculty based on the campus; that it would be temporarily divided because it would take time to generate the capital funds necessary to build a hospital on the campus. And people talked in terms of ten years before that could be expected to be accomplished. Meanwhile we would straddle the city.

Int.: That seemed reasonable to you?

J.F.: Yes. Yes, we had a very optimistic expectation that everything would come up roses in that particular way. And you will recall that the School began in the very early 1950s when we still had the postwar – well, I suppose it was the Liberal Government at that time. There had been the coalition. I think the coalition had broken down, but it was before the coming to power of the Social Credit government under Mr. Bennett which then held power in the province for the next twenty years.

Int.: I don‘t recall when Mr. Bennett came to power…

J.F.: ‘52.

Int.: Do you think that held things back a great deal?

J.F.: I’m not sure. I’m not trying to assign responsibility. It’s just that it was a different government which didn’t have whatever previous commitments the previous governments may have had. So it was all up for grabs…

Int.: Well, I guess they hadn’t gone through a lot of the preliminary talks. Either you had to start at the beginning…

J.F.: So it had to start from scratch.

Int.: Maybe, you could tell us a little about the circumstances of your recruitment. You say you arrived at the end of the first year.

J.F.: Yes, the School began and the first year was taught and nearly completed before the personnel to carry on the second year were in place. It was rather – I don’t suppose ‘disorganized’ is the word – but everything was being done in an ad hoc, step-by-step, sort of way and it was in, I think, late April or early May in 1951 when I was a post- doctoral research fellow at Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York, that Marvin Darrach, who was at that time professor of biochemistry and was on a trip east for various purposes. I think that he still had some connections with the industrial firms that he had previously been associated with, perhaps a consulting arrangement. In any event, he was visiting in the east. He had been asked by Dean Weaver to come to Columbia, to approach them about the possibility of recruiting a very prominent, young pharmacologist who was at that time assistant professor in that department, a man by the name of George Cooley, who later on became the head of the Pharmacology Department, and later dean of the Medical School at the University of Pennsylvania. He was a very bright and promising young pharmacologist. They had no one at that time to teach pharmacology three or four months from then. Dr. Coley had just come to Columbia the year before and had a very promising career there and was not interested in moving. Marvin came in to see my sponsor, who was also a sponsor of Dr. Coley, a man by the name of Alfred Gilman who was a very prominent American pharmacologist and co- author of the standard textbook in the field, (he came in) to ask him for suggestions and he was kind enough to suggest me. I remember Marvin coming into the lab where I was working, doing an experiment on a dog, a surgical experiment and I was spattered with blood, in fatigues and so on, labouring away. He was introduced to me and we chatted briefly. As a consequence of that contact, I was invited to be interviewed and I did, and I was offered the position.

Int.: Who was the actual invitation from?

J.F.: From Dean Weaver.

Int.: That was from the dean, not from the president?

J.F.: I am sure it was from the dean, yes.

Int.: You mentioned earlier that the impression you were given when you came was that you would have a medical school centred on the university, with perhaps a hospital within ten years?

J.F.: Yes.

Int.: Was that impression given, then, by Dean Weaver?

J.F.: Oh Gosh, I don’t recall him making such specific suggestions or commitments. I’m sure it was discussed as it was with all people that I spoke with, and I probably received my own impressions and expectations more from the atmosphere of conversation I got from the other equally young, optimistic basic scientists such as Sydney Friedman, Harold Copp. We were all of about the same age, relatively young for being given those kinds of opportunities and challenges which we were being given. It tended to generate a kind of a hopeful esprit-de-corps.

Int.: It must have been quite exciting really.

J.F.: It was. It was an exciting time. It was exciting for two reasons. One was that the School was first starting and was being manned by relatively young persons and the other was that its class composition, the students, were the first postwar students. They were, by and large, an older and more mature group of students than you would normally see entering a medical school class. They had, very often, been waiting for the school to open in order to begin their medical education. They too had a very actively and vigorous approach, eager, and that combination made for an exciting mix.

Int.: Yes, I can understand that. Do you think then, that the students in those first couple of years were more enthusiastic, a little keener, than the students in previous years? Did you really see much difference?

J.F.: I think that they were somewhat unique in that they had had to wait a bit for it. And because they were a part of starting something new, I think they also were affected with overcoming the practical difficulties that we were faced with in beginning that. When you start a medical school in which the courses are being taught by one or two people, on a shoestring almost in terms of physical circumstances and equipment, there are practical problems which have to be overcome. The students have to cooperate in overcoming them and it generates a good spirit of excitement and enthusiasm.

Int.: There must have been quite a closeness between the students and the faculty?

J.F.: I think there was. In part because there wasn’t such a big generation gap and also because there was a sense of a common enterprise: we were in it together; we were going to make it.

Int.: Did you find, thinking back, that those students were quite well prepared for medical school, any more prepared than students now, or not?

J.F.: I’d say equally well. And they had the advantage, many of them, of a greater degree of maturity. Many of them were veterans, had served in uniform during the war. And perhaps that made it financially possible for them, with veterans’ benefits, to tackle an education that they might not otherwise have contemplated. So it was in many ways those early classes that were very good classes. They stand out in my mind, perhaps more because they were smaller with sixty students in a class, so it was easier to get to know them individually than with the 160-some odd we have now in medical/dental combined classes. At that time also there was the – well, I’m not sure how to phrase it; in any event there was the expectation that some of these students might go on in themselves into academic medicine. And there were opportunities for them to work with us in our research labs in the summer. We were all keep to recruit better students into academic medicine and some very outstanding young people did come out of those early years and go on into academic medicine, some of them at our own school, people like Ralph Christiansen, one of the prominent people in our Department of Surgery now, who was one of the top students in our first class; Bill Webber was one of our early medical students; Frank Tyres, who is the head of our Cardiovascular Surgery, was a graduate of those early years – not the first years but the early years when we were over in the huts, and a number of others.

Int.: Does that not happen so much now?

J.F.: I think less so, and of course there are complicated reasons for that. I think that academic medicine appears somewhat less attractive, particularly basic science academic medicine to contemporary medical students than it did to students at that time. Just as the academic life generally doesn’t look as promising now for young people.

Int.: Well, I suppose there aren’t as many opportunities, or people don’t see that there may be opportunities…

J.F.: They see the opportunities contracting instead of expanding. In those days they were expanding.

Int.: What about getting your Department off the ground? Actually, just before we go on to that question, you said that you came here the end of 1950 and, it might have been a slip, you said that you talked with Dean Weaver in 1951.

J.F.: 1951. The School began in 1950 but I came here in 1951.

Int.: So that was the correct date that you mentioned?

J.F.: 1951, and I moved here within a couple of months after my initial contact. I came out here in May, and moved out here with my wife, and our daughter who was born in March of that year in July, across the continent

Int.: That must have been quite exciting with a new baby, a new job, a new city, a new country.

J.F.: Exciting, but it had its difficulties too.

Int.: I can imagine. Well, you were the first person recruited for your Department, weren’t you? So you had to basically do everything to get it going.

J.F.: The first year I taught pharmacology. I gave some 60 to 70 lectures which all had to be prepared from scratch, and operate a laboratory which met twice a week for a full semester. Some twenty odd laboratories, with the assistance of a single fellow, a teaching fellow from the Department of Anaesthesiology, who was an excellent helper, John Chang, who is still member of the Anaesthesiology Department here. The arrangement had been made before I came and I suppose in part is attributable to Digby Lee, who was the head of Anaesthesiology at the General Hospital at that time, and it was then a Division of the Department of Surgery. He was a very vigorous and enlightened physician, very keen on the teaching side of his responsibilities, primarily for the interns at the General Hospital. So, in addition to my teaching the medical students he had to be helped at the Vancouver General Hospital about once a week to give basic science refresher lectures to his anaesthesiology residents.

Int.: Well, it certainly sounds like you were busy.

J.F.: He had made this arrangement that he would have one of his residents come out to UBC each year and be a teaching fellow. And he divided his time between physiology and pharmacology initially. Later we each did our separate thing. But he had some responsibilities to them as well, and he was extremely helpful in setting up and operating that laboratory.

Int.: What did you have to do to set the laboratory up? I understand it would have been in one of the huts, which was basically just a bare room, wasn’t it?

J.F.: Hell, we had a large room. I guess it was about the size of this room, and we had flat benches in it and we took sixty students at a time into that room, and we had old- fashioned smoke drum kymographs which the Physiology Department had secured, and we shared facilities with the Physiology Department during the entire period we were in the huts. We had a common laboratory which we shared, but we had gradually been disentangling ourselves over the period of time. We had a common secretary. We had a common shop. We had a common technician. And bit by bit over the years we acquired each a secretary, although they shared a common office during that period of time in the huts. We acquired separate shops and shop technicians. We gradually separated.

Int.: It grew from there… What kind of problems, if any, did you run into at the beginning?

J.F.: I suppose the major problems were just those of the shortages, the physical circumstances and the divisions which that required. You see, the facilities that we began with consisted of the laboratory where the students had to be taught. There was an office, the secretarial office in between, an office for Dr. Copp who was head of the Physiology Department, and an office for (me?) and there was a laboratory in that building which Dr. Copp had research work. He had only one other person in the Department at the time, Dr. Edgar Black, who had previously been in the Zoology Department here and who did not, I believe, at that time have a separate research laboratory. Or if he had research facilities they were in connection with Zoology; he did not have a lab there, nor did I. And I was promised I would have a research lab. A relatively small room was provided for me in the building that Biochemistry was occupying. Biochemistry at that time was in the tar paper hut over here where the Home Economics building now is, approximately I think. I was told that I could have a smaller room for a laboratory adjacent to that, which I would use when I was able to recruit a second person in the Department, which I was told I could do for the following year. When that person came he shared a small room next to my lab for a year or so, then we were gradually squeezed out by the needs of Biochemistry and we had to find other research laboratories. Dr. Daniels, who joined me in 1952, at the end of my first year here, was given a year or two later a laboratory space in what had previously been the fire hall, which was back behind those huts. And then a year or so later I was given a research laboratory further back on the West Mall which was a piece of a building then in the hands of the Mining and Metallurgy.

Int.: So these research labs you were given were some way from where you…

J.F.: We were scattered around a bit, not far apart but…

Int.: Enough to make it inconvenient…

J.F.: …some inconvenience. It wasn’t great but you weren’t able to step next door and talk to your colleague. You had to make a trip.

Int.: So do you think that these physical circumstances hampered your research or your teaching?

J.F.: No.

Int.: They were just difficult?

J.F.: They were just difficulties that had to be overcome, that’s all.

Int.: What about Dean Weaver? What was his role in getting your Department off the ground, or did he really have one once he recruited you?

J.F.: I think that’s very hard to say. A dean always has a role because a dean has the responsibilities and the authority when it comes to budgets, to making assignments of space, all of the academic decisions that have to be made, at least channeled through the dean. Of course, we had a faculty council on which all the department heads sat and hammered out things together.

Int.: Do you think a lot of his decisions were good decisions for your Department?

J.F.: The best way that I can put that is that I don’t think that Pharmacology occupied a particularly high place in Dean Weaver’s scheme of priorities. There was some uncertainty at the time that I was being recruited as to whether or not Pharmacology would, in fact, be a separate department or would be a part of a combined Physiology/ Pharmacology department. One of the conditions of my recruitment was that we would indeed have a separate department. There was always the struggle – as there always is between department heads and deans – over budgetary matters, over space, over facilities. Maybe those are less complicated, less personalized today than they were in those days, when it was pretty much a one-on-one proposition. The department head went in and tried to sell the dean on what he thought he needed, and he either was persuasive or not. Nowadays there are committees and so on which deal with those matters and I think there is less of a one-on-one.

Int.: They don’t feel the same way, I imagine…

Do you think the Faculty of Medicine was prepared enough for students when it opened its doors to the first class – not just your department but your department and the Faculty as a whole.

J.F.: Surely it could have been better prepared and it could have been housed in a handsomer facility and things could have been bettered. But I think that, given the circumstances at the time what it took to get a medical school started here, that it was a good thing that they went ahead with it and that it was given the opportunity and grew. If they had waited until everything was in place, I’d have waited a long time; who knows what would have happened. So I think it was adequate and I think in some respects given, as I say, the enthusiasm that was generated in overcoming the obstacles, that the outcome was good and maybe better than it might have been under more favourable physical and financial circumstances.

Int.: You mention the financial circumstances. Did you find there was enough money to do most of the things you wanted to do in your Department?

J.F.: You never feel there is enough. You make do with what’s available and…

Int.: Hope that there’s more coming?

J.F.: Right, so you scramble along.

Int.: What were some of your specific expectations when you came here? And do you think those were met?

J.F.: Well, I think the main disappointment was with regard to the emergence of an affiliated hospital on the campus which, as I say, was something that I was hopeful for from the very beginning, something that I thought would be very important to the growth of the kind of medical school which I would like to have seen here. My vision was that British Columbia was like California, or the United States, or the West Coast, full of promise and energy, and that it had the potential for becoming a medical faculty of outstanding excellence. I think it has become a good medical school and from time to time has had very excellent aspects to it. I don’t think it has fully lived up to the potential that I thought was there at the beginning and, while there are outstanding medical schools in North America which are on separate campuses from universities, they are generally schools where the basic sciences and medical facilities are united in a single site. I think that could have happened here and that site could have been elsewhere than on campus. I don’t think it would have been the best thing if that had simply been the General Hospital because a general hospital is not the best site for the academic heart of a medical school. It’s gotten too big and it has too many other responsibilities to develop the kind of concentration on the research and scholarly aspects of medicine that I think are necessary for excellence and which I feel, with all due respect to those who feel that this is perhaps an elitist point of view, that aspiring to excellence in the educational facility that serves the Province is the best guarantee of the overall quality of professional standards and professional service in that area. I don’t think we have succeeded as well as I hoped we might in providing that kind of facility.

Int.: It’s interesting what you say because it sounds like you think they might have thought of setting up the medical school at a different hospital than VGH.

J.F.: No, I don’t think under the circumstances that would have been possible because of the professional, political power structure in Vancouver at that time.

Int.: That’s what I was going to say…

J.F.: It was certainly not in the cards. And I think this is perhaps one of the reasons that a number of those coming to the campus at that time, particularly in the basic science areas, clung to the campus as the place where there was the best opportunity to develop a consolidated school with both clinical and basic science facilities on the same site but not at the General Hospital.

Int.: So that would really have been your…

J.F.: So this, of course, was the bone of contention over the next considerable period of time because of course the clinical people wanted better facilities in which to work and having only the General Hospital to site them, wanted to continue to build up what they had there. And those of us who foresaw what we viewed as not only the ideal but the necessity of getting clinical facilities on campus, always felt that the more that was done there the harder it would be to wean it back to the campus.

Int.: Do you think that actually did happen?

J.F.: I’m sure it did to some extent. It was inevitable that it would, and without wishing to assign blame if I had been in their shoes – I’m speaking now of the Commission’s – I would have wanted better facilities in which to work. If I felt it was inevitable that they had to be at that site let us have them there – don’t be dogs in the manger. And we might never have had even what we’ve got here now if it had not been for the strokes of political fortune that ultimately led to – basically – Pat McGeer cutting the Gordian knot and saying “There will be some kind of a hospital on campus.” I have many, I’m sure, very sharp differences of opinion with Pat McGeer on many things, academic and otherwise, but I think that if he’s only done one good thing in his life that that would be it. I’m sure there are a lot of people who dispute that view and think that that was a disastrous thing to do, but I think, over the long haul, it keeps open the door for having at this site at some time in the future a fully developed clinical unit which will serve as the kind of model that I…

Int.: Can you see that happening?

J.F.: Yes, the door is open. Nothing to prevent it happening except the political and professional will and understanding of it.

Int.: It’s really taken quite a lot longer than, say…

J.F.: Oh, it has.

Int.: …people who wanted the hospital at the very beginning, those who didn’t want to start the medical school until a hospital was built, certainly wouldn’t have thought it would take as long as it did, I would imagine.

J.F.: Right. And, of course, this was part of the reason for the turnover in administrative structuring in the early years when Dean Weaver became relatively incapacitated and unable to carry on they brought in, as you know, a young person from the Western Reserve system, full of gung-ho and stirring up a ferment about medical education. He was committed to trying to build hospital facilities on campus and I felt within a year or two he felt that those commitments were not going to be met and baled out.

Int.: This was one of the things I wanted to talk about. Maybe we should veer off a bit. This is Dean Patterson you are referring to?

J.F.: Yes.

Int.: Maybe you could tell us a little bit about what you thought some of his ideals were?

J.F.: I think they were two-fold. I think his recruitment here – I think Sydney Friedman was very instrumental in his coming because he knew him as a fellow anatomist – and I think he had become very much involved in and perhaps committed to the Western Reserve way of doing things in medical education. They were a pioneer in innovating a different pattern of medical education along functional rather than disciplinary 1ines, inter-departmental teaching and that kind of thing. There are a lot of pros and cons on that method. It’s very time consuming to try and organize that type of teaching interaction and it cuts across conventional ways of organizing administrative, academic structures. So there were a lot of problems with doing it but he was all for trying it and it did stir up a lot of soul searching and self-examination about our medical techniques. We were planning then buildings and designing the ways in which laboratories would be arranged, and would they be interdisciplinary laboratories or would we have the separate departmental ones. And I think the architects got a lot of fees out of planning interdisciplinary laboratories at that time, which were going onto the drawing boards and which we were hopeful would be built. But I think that Dean Patterson was also persuaded of the importance and the necessity to create clinical facilities in connection with them on the campus. And I think he felt that either the commitments or the expectations that he had been given weren’t likely to be realized. And after a couple of years he pulled out.

Int.: Do you think that was specifically why he left; he just didn’t think it would turn out the way he hoped?

J.F.: I have no doubt that was the case, and he felt he had good reasons for thinking that. Now, Sydney Friedman could probably remember better and tell you more about that than I can. I think he was closer to Jack Patterson than I was. But I am confident that he shared that same aspiration and expectation that I did and was equally disappointed that it didn’t turn out as we had hoped.

Int.: What about – just to go back again to Dean Weaver – Can you tell us something about him?

J.F.: I was never very close to Dean Weaver and I think it would be unfair for me to try and say very much. I don’t really have that accurate a memory. I found him from time to time a somewhat difficult adversary, because I felt we had somewhat of an adversarial relationship from time to time, and I just didn’t think sometimes we were on the same wavelength. I think he was primarily, I would say, a good housekeeper as a school administrator rather than a person of very great vision or very great vigour in pursuing a vision. And yet, at the same time, he came out here to start a new school and accepted that challenge and recruited, I think, some very good people. I think he showed a lot of imagination in bringing Bill Boyd in, post-retirement, to begin teaching pathology here. And I think that that contributed a great deal to the spirit of the school because Bill Boyd was an exceptionally good teacher and very much concerned about the students and their welfare. I think it added a lot to the feeling of rapport between faculty and students that existed through those years. So I give him credit on those scores but there were other things that I personally found difficult.

Int.: What about his attitude towards the split school? Do you think that he had expected that, or was he able to work well with that compromise, or do you think it bothered him?

J.F.: I’m not sure what bothered him and I really don’t think I can speak with much confidence about what was in his mind in that connection. I think he was a rather pragmatic person and probably took things in his stride and worked with whatever…

Int.: Reality and simply accepted it…

J.F.: Yes, that would be my guess but then I’m reluctant to do much mind reading. Int.: What about Dean McCreary, since we are talking about deans?

J.F.: Let me be very frank on this. I felt that when Jack Patterson was the dean and was driving hard to try to create hospital facilities on the campus – and at one stage he was contemplating just putting a paediatric hospital here – that McCreary was in opposition to that. I recall there was an occasion when we had a meeting over at the old faculty club, which was in a hut overlooking the inlet where the new club now stands, and these things were being debated. I thought that he took a rather negative view at that time. And so, when he ascended to the deanship, I was somewhat disappointed that we hadn’t gone out and gotten someone from outside in the image of the Jack Patterson kind of thing. But over the years I came to acquire a great respect for Dean McCreary and I think that in his way he was working toward these objectives but was perhaps more pragmatic and more willing to wait and be patient and so on than I would have been. Because I think that he did try to build up the school. As a matter of fact, I think that my different appraisal of Dean McCreary was responsible for the growth of less intimate interaction and support between persons such as Dr. Friedman and myself than we had before because I think Sydney was never able to fully reconcile himself to Dean McCreary’s deanship. There was more tension between them and I think Sydney may have felt that I had lain down when I found it easier to work with Dean McCreary over the years. But I found him non-adversarial. Perhaps this is a reflection of my own personality. I prefer working with people in a non-adversarial way rather than in a confrontational sort of way. I always found him willing to listen and to be sympathetic with your aspirations instead of, as I sometimes thought Dean Weaver did, if he didn’t feel he could supply you with what you wanted he tried to argue that you shouldn’t expect it or want it rather than to say, Gosh, I wish I could get that for you. 1’ll try, but don’t be optimistic. McCreary was more apt to be the other way.

Int.: Sounds like McCreary would at 1east make you feel better about it.

J.F.: That’s right. And maybe this made me more tolerant of whatever shortcomings he may have had in other respects.

Int.: Sounds to me in some ways he was quite good in dealing with people, then?

J.F.: I think so. There were persons that he had conflicts with. I think this bothered him. I think he too preferred…

Int.: …to work it out in a pleasant sort of way…

J.F.: Yes. I came over the years to be rather fond of him.

Int.: It seems it was a period of a lot of growth in the medical faculty when he was dean. Now do you attribute that a lot to him or to what was happening at the time?

J.F.: I think he had a lot to do with it because I think that he had considerable powers of persuasion and persistance and instead of getting people’s dander up by antagonizing them he would mollify them but continue to try…

Int.: Keep at it.

J.F.: Yes.

Int.: So it sounds like those three deans that we were talking about in the beginning were all quite different really.

J.F.: And of course we had interregnums when we had no dean and when Rocke Robertson was holding the fort.

Int.: How did that work out?

J.F.: Well, let me say this. I have tremendous respect for Rocke Robertson. I think he was an exceptionally fine person and excellent clinician and again did his utmost to fulfill his responsibilities. But I don’t think his heart was in deaning, at least at that time. Of course, later on he went on to become principal of McGill University and to become an administrator. But maybe that summit position had more attractions for a person with his background than simply being the dean of a medical school. He divided his time, you see, and continued to be the dean of the Department of Surgery – sat in as dean pro tem but nevertheless he was very good. We had some crises during that time when we had conflicts with Biochemistry over our competition for space and our need for research labs and so on. And he would go out and resolve those by getting additional space somewhere, scattered halfway across campus but he’d get something for you! He delivered the goods!

Int.: What about the buildings that were finally designed and built. I think that was about 1961?

J.F.: ’61.

Int.: Did you have a lot to do with the design of the buildings. Did you have a lot of input yourself?

J.F.: No, we each in a way were allowed to design our own buildings, more or less, in consultation with the architects. Of course, the general architectural features were decided by them. Few of us would have selected the particular array of panels that they put up outside those buildings (laughter). But by and large we were within the overall space that was allotted to us and we were allowed the design things the way we wanted to and we each did things in our own way, whether wisely or not.

Int.: Well, that’s sort of the next question. Do you feel that you got a good working building, something that you wanted?

J.F.: I think so. And while it has undergone a number of remodeling since then, the buildings lend themselves to permitting that and I think that they have worked out reasonably well.

Int.: What’s your feeling on having separate buildings? I presume at the time, the idea of having one building was discussed and – you know – different plans brought up?

J.F.: You know, there were many plans that were looked at at that time, and some of them had us all in one building, some even a tower, and others not. I believe that it has worked out for the good. We’ve had each department more or less in a separate building. It has provided a certain spatial image for each department. I think it has lessened the contentions which otherwise might have developed. You see, each of us was, in our own way, concerned with building. And when you want to build, you want to overcome all the obstacles that stand in your way. There’s always the element of empire building that can intrude into that, and empires tend to be built at other people’s expense! So if we were all in the same building people would be eyeing one another’s unused space covetously and maneuvering to try and secure it for oneself. And I’ve seen this sort of thing happen at other institutions, where I’ve known the personnel there and known the frictions that can arise when those opportunities for conflict are present.

Int.: Do you think a lot of this was eliminated by the designs that were chosen?

J.F.: I think it helped to minimize that possible bone of contention between…

Int.: On the other hand, do you think there was less communication between departments where it may have helped out in research or – you know – just discussing everyday things?

J.F.: Yes, perhaps so. But if people are inclined to want to work together, small amounts of geographical separation can be overcome if the desire is there. And if the desire is not there no amount of proximity is going to bridge the gap.

Int.: I imagine, coming from the huts to the buildings you were used to more difficult divisions than what you have here. I suppose you were used to that and able to deal with it. What about the relationship between the University and the hospital; the general practitioners and the basic sciences? What would you say about that?

J.F.: When you say the University, you mean the basic sciences, the medical sciences?

Int.: Part of the medical faculty.

J.F.: I’d say there hasn’t been much relation.

Int.: So it couldn’t have been bad (laughs) if there wasn’t much! Do you think not having a relationship is a bad thing or a good thing, or has it really affected you in any way?

J.F.: Well, I’m not sure how I should respond to that. I think we all come out of different backgrounds and have a different mind-set as to the particular images we have and the ideals of what we would like to see happen. My experience at previous institutions as I say perhaps gave me somewhat this elitist notion that the academic medical institution should be example, that it should provide a model of the very best in medical care. That to do that it had to have absolute control over the particular clinical facilities in which that work was being done. That it had to have sufficient budget that it could command a generous share of the time of outstanding clinicians who would not be torn between the temptation to spend time in patient care as a source of revenue but would have a sufficient amount of their income paid so that they would be free to choose how they would spend their time in order to best serve their academic needs, between their research and practice and teaching. And this requires sizable budgets because of the very large incomes which good clinicians can demand in service. These things are hard to come by. We didn’t have them in the early years and perhaps we still don’t. I think that there is a source of inevitable contention if not conflict between that image of an academic medical institution and the image which a great many members of the local medical profession see as the sort of institution they wish to interact with and to have a foot in the door of and not to see clinical facilities which are closed to them. I think there are probably ways of reconciling these competing needs but they are not easy to reconcile and I think that apprehension about them has led to less enthusiasm for the kind of academic medical institution than I would like to have seen among large numbers of influential local medical practitioners.

Int.: Would you say also that the conflicts that were set up before the medical school even began led to all of that – that it would have been difficult to change that with the beginning that it had?

J.F.: I would expect so, yes.

Int.: So do you think that a working relationship between the medical school at UBC and the Vancouver General Hospital was worked out in the end?

J.F.: Sure. A relationship was worked out and has persisted to this day. We still must do a substantial part of our teaching there, and we should. But my feeling is that it has remained in a number of areas still too much “the base” and I think that a large community hospital of that type preferably should be the ancillary rather than the fundamental basic component of the clinical teaching. We will, for at least a long time in the foreseeable future be a school whose clinical teaching facilities are – and now I’m speaking of the core clinical facilities – are divided between several sites with the paediatric OBGYN area in the Shaughnessy site and substantial parts of the medical/surgical/psychiatric and other areas at the VGH.

Int.: You said at the beginning of our discussion that you did go out to Vancouver General to give one lecture a week. Did you have any other contact with the hospital yourself other than that?

J.F.: I may have occasionally been asked to contribute to a Round in the Department of Medicine if it was on some topic that I knew a little something about, but very little.

Int.: Do you think it would have been better had you had some more contact?

J.F.: Again, given the geographical distances it would probably have been difficult. I think ideally there should be a very close contact between what’s going on in basic sciences and what’s being done in clinical departments. The atmosphere in which I had my training years was conducive to that sort of thing: to Rounds in which the basic scientists were always present and active contributors. And this opportunity now exists to some extent with Rounds being given here in our Acute Care Hospital. But they are not widely advertised among the basic science departments. You hear about them sometimes and go over to ones you are interested in. But I don’t think that has yet been cultivated as much as it might have. But surely the opportunity and potential is there and sooner or later I’m sure that it will be realized. The advantages I think are sufficiently…

Int.: Something that people are aware of. Maybe it takes a little while to get it organized.

J.F.: …obvious.

Int.: What about curriculum planning? You say you did all of the teaching in your department to begin with so I imagine you were the one who planned the courses as well ?

J.F.: Yes.

Int.: Is there anything you would like to say about that?

J.F.: Well, of course. Every School periodically does soul searching about its curriculum and this is a healthy thing. I think it seldom leads to fundamental changes and may not lead to any changes at all. But I think it helps to keep one’s sensitivities out to keep thinking about the reasons one is doing what one is doing and the way one is doing it.

Int.: Did you feel satisfied with the way the courses were going in, say, the first year? It sounded like you were very, very busy. You were doing all the labs and all the teaching, but basically do you think it was successful?

J.F.: Well, I would like to think so. I am reluctant to say. Yes it was. I think that the proof of that is in the product and that’s difficult to say. I think that our Department over the years has taught a good course. I think it has not always been evident to students taking it at the time that it was so. We usually get more praise for it afterwards from people who say later on, Yeah, that was important and I learned a lot. But this is because it has a large information load whose relevance they will need in the future is not clear at the time and they only see later what its importance is. And I think that’s a reflection, perhaps, of insufficient interactions that I’m speaking of between basic science areas.

Int.: Did any of the clinical appointees make an effort to come and see what was happening at the university site?

J.F.: There were some, but not very much really.

Int.: Not as a general rule?

J.F.: As I mentioned, Digby Lee was outstanding in terms of his sensitivity to basic science and its usefulness to his area of practice, anaesthesiology. I don’t think that the others were necessarily insensitive to it but, again, these geographical separations and the other difficulties didn’t lead to very much exploration and exploitation of that potential, in my view.

Int.: What was the relationship between the existing science faculty and the basic sciences and the medical faculty? Was it a good relationship? Was there communication? Was it necessary to have communication?

J.F.: Useful but not necessary. As I say, there are outstanding medical schools on this continent in which the medical school has been completely separate from university campuses. The school I went to, for example, and Harvard, and a lot of others. But there are potential advantages from being on a university campus and interacting with basic science departments. That advantage is perhaps not easy to realize or to exploit. One does see it in some areas. One that comes to my mind that I am aware of in recent years has been the growth of what’s called a biomembrane group, which has brought in people from Physics and Chemistry with people from Biochemistry and Physiology and Pharmacology, who have a common interest in a particular area. One can see it, I think, in the new imaging devices that involve nuclear magnetic resonance and positron emission tomography and that kind of thing, which do involve very important, basic science instruments and efforts to apply them and use them in clinical medicine, and the whole TRIUMF facility and its relationship and usefulness to clinical medicine. So there are some areas where this can be done and some of them have been realized. But it’s grown much more slowly and much less actively than might have been ideal.

Int.: What about the allocation of money? Do you think that other faculties in the university might have thought at the beginning that a medical faculty would take money away from them?

J.F.: No doubt. No doubt, and they may have been right, I don’t know.

Int.: Do you think they were, in spite of feeling that they wanted a medical faculty?

J.F.: Some did and some didn’t. But I think that it was viewed, and perhaps again with some reason, as a gilt-plated area that would attract money, money that might otherwise be available for other academic needs. I’m not sure this is true but I think the apprehension was there and there were reasons for it. And I think it has probably persisted right on through, perhaps with lesser emphasis in recent years than in earlier years. I’m sure it has existed.

Int.: What about the allocation of resources with the basic sciences and the clinical part of the medical faculty? Was there any conflict there?

J.F.: There’s always conflict in that there’s only a limited pie to be cut up and someone has to decide how to slice it.

Int.: Let’s say, did one or the other feel they weren’t getting a fair share? Or did it seem like it was fairly divided?

J.F.: They may have. I think in the earlier years when we were – when administration was largely rather centralized, one often didn’t know what the pie was, whether one’s share was fair or not. One simply went in and pleaded one’s case. If one saw someone who seemed to be getting off better than one was, one could demur as to whether or not favouritism was being played or whatnot. But one really had no basis for judging. I think that later on, particularly after McCreary became dean, some of these budgetary procedures became more open. People became more aware of what the pie was and how it was being sliced. I haven’t personally felt discriminated against and I don’t know of any grounds really of a strong feeling that there has been particular unfairness in allocation of funds.

Int.: Just to go back to talk about the students for a bit. Did you have very much to do with choosing the students, who would enter the medical faculty?

J.F.: No.

Int.: You didn’t?

J.F.: I was never involved in that process. There was one time, I guess about 8 or 10 years ago, when Dean Graham tried to entice me into that area. I resisted.

Int.: OK. There’s no point in going on about that then.

J.F.: I think it’s very important.

Int.: But I think there are other people who have been involved in it. I guess it was Admissions that I was thinking of, particularly.

J.F.: I think it’s very important. And from time to time I’ve demurred from certain practices that I felt that Admissions committees had fallen into. Maybe that’s why Dean Graham wanted to show me how difficult it was. As he used to say, it’s easy to know why anyone wants to go to medical school. Ask any aspiring student why he wants to go into medicine. He’ll say, It’s because I love people and hate money.

Int.: (Laughs). If you asked somebody on the street, what would they say?

J.F.: It’s difficult to choose, and my feeling is one should rely heavily on academic performance but I recognize that this is only one of the yardsticks by which one would wish to measure the qualifications of people whom one would like to see in medicine. But how do you measure people’s humanitarian inclinations? When they know what you want them to say, it’s very difficult for them to… That’s what Dean Graham was implying. And if you can’t measure that, what else do you have to go on? But as you know, in recent years competition to get into medical school was so intense that it became notorious for the backbiting and nasty nature of that competition that would often develop. And one heard rumours of students in chemistry classes spiking one another’s unknowns in order to give oneself a better chance of getting a good mark.

(They both laugh.)

Int.: Was that competition of the same type there when the medical school first started, or not?

J.F.: You mean, to get into medical school?

Int.: Um-huh. Was it as competitive?

J.F.: I don’t know. I think it’s always been competitive to some extent.

Int.: What about — again, some of the things dealing with the students. One item that I read about was a thesis that was required from the students in the first few years. And then it was dropped. Why was that? Why, first of all, did they have it?

J.F.: Well, I think it was thought, and probably by a model from somewhere else, that it was a useful academic enterprise and gave the students some focus of creativity, some scholarly undertaking on their own that required a certain amount of independent exploration and reading of some medical literature, and the putting together of an argument. I think these were all very good reasons for wanting to do that sort of thing. I think the majority of the students viewed it as an additional burden whose relevancy was not apparent to them in terms of their image of what a doctor needed to know and to do and their resistance built up over the years. And that was largely responsible for its being dropped. I think we still have a hiatus and a gap, which is prominent, if you have seen the most recent critique of North American medical education. Our own medical facility was circulating something recently on this, that we are not producing the self-educating physicians that we should be. How do you make people self- educating if you don’t give them some opportunity to participate in their own education in some way? Some way of directing and training then to learn how to read and analyze and think critically about what they read. That essay was one way to try to meet that objective. I think we do have too few of those opportunities in contemporary medical education.

Int.: They weren’t actually required to do the thesis for very long, were they? It didn’t seem to me. Only about four years.

J.F.: I would have thought longer than that, but I have forgotten just when it was cut off. You should be able to locate that in the records. I would have thought it was longer than that, but I’m not sure.

Int.: What about the medical illustration department? I understand there were some problems with that in the beginning. Do you know anything about that?

J.F.: I think there was always, as there is with every new development, an apprehension that it is going to grow and take funds away from others, and that it will be an empire- builder on its own, and what it would do could be done just as well in some other way. And of course we had some photographers on campus or at the General Hospital and some people who would help with medical illustration. And I think it’s been a mixed bag. I think to some extent the apprehensions people had about the development of that kind of facility of becoming an empire of its own are true and yet I think it has performed a very useful service. And it’s been a good thing. Whether it’s been more expensive than it should have been, whether it’s one of those things on the hit list – expendable – …

Int.: It’s hard to say.

J.F.: We found the people there always cooperative and helpful. As long as we can afford them it’s a good thing.

Int.: Can you think of any little anecdotes – just things that would be of interest to people – looking back to the beginning of the medical school, that happened to you, or in your Department, or just anything that you can recall. I don’t know – I remember, Dr. Copp told me about frogs getting out of his tank and being all over the parking lot. He was all dressed up in his tuxedo coming from dinner… Those kind of things, I’m sure, wouldn’t happen now. They’re the kind of things that could only have happened under the circumstances when the medical faculty started. I was wondering if there is anything you can think of?

J.F.: I don’t think so. As I mentioned at the beginning, I’m not much of a nostalgia buff or memoir type. Those kind of things – I’m sure that there were a lot of episodes like that in my experiences – but they don’t stick much in my mind.

Int.: Can you think of any other things that you think should have been recorded? About your Department getting started? About your arrival at UBC? Any other specific things?

J.F.: No, I think the only thing that sticks in my mind is that we were a much smaller enterprise at the beginning. And I would say, not only the medical faculty – because it was true of the medical faculty – but the University was smaller, about 7 or 8,000 students, something like that. So that there was a much more intimate atmosphere. I recall, when I first came here that all new faculty were entertained at a dinner in groups of maybe eight or ten at a time, by the president of the University at the Vancouver Club. A very, very nice dinner and an opportunity for people to say a few appropriate words to one another about their joint undertakings, so that one knew the university president more personally. I think nearly every faculty member was known to Norman MacKenzie. His door was always open to any faculty member who had a problem and wanted to talk to him about it. Faculty Association meetings involved – I don’t know if they involved a larger number of faculty – I think on a proportionate basis they probably did in those days. And people from different parts of the university seemed to get to know each other more quickly and better than I think they do now we have grown. I think we are too big a university now for ideal. I think about 15 to 20,000 was about as big as a university should be to be the best it can be. Then you begin to get too big and the bigness gets in the way.

Int.: Do you think that the medical faculty is too big now?

J.F.: Yes, I think so. I think 80 to 100 students is probably better than 120 to whatever we are supposed to be in terms of… I used to know the name of every student in my class. I could recognize them from the back of their heads sitting in a lecture hall. I used to make it a point to do that. It was easy to do that when you had 60 or even 80 students. When they begin to get larger than that it becomes more difficult.

Int.: I can understand that. I think you might have answered this question already. Do you think the goal of a first class medical school has been reached or will be reached?

J.F.: I’m sure it will be. And there are some who would debate whether or not it has been. I think it has been pretty good and I don’t think we have any cause to feel shame. We’ve done better than a lot of other medical schools. I don’t think we’ve been as good as we could have been or as I would like to have seen us.

Int.: Thank you very much, Dr. Foulkes, for contributing to these tapes.

| Interview date: Tuesday, March 12, 1985 |

| Interviewer: Sharlene Stacey |

| Transcriber: Patricia Startin |

| Transcriber to PDF: Suzan Zagar |

| Funding: The Woodward Foundation |

| Identifier: Book 1 |

| Biographical Information: Dr. Foulkes was recruited to UBC as a Professor of Pharmacology in 1957 and remained for the rest of his career. |

| Media: Transcript: Interview with Dr. James Foulkes (.pdf) |

Summary:

The early years teaching in the medical school; the students; research laboratory space in the 1950s; a campus hospital; Deans Patterson, Weaver, and McCreary; medical essay requirement; opinions on university and class size.